Grey Teal Anas gracilis

Category A; Common and widespread resident and winter visitor.

Common resident of wetlands and waterways across Brisbane. More records in winter, suggesting a degree of migratory behaviour, although occurrence fluctuates year-to-year. Breeds during spring and summer. Not of conservation concern.

| Threat status | Brisbane status |

|---|---|

| IUCN Least Concern | eBird records 8,561 |

| National Not listed | Atlas squares 98 |

| Queensland Not listed | Reporting rate 12% |

Marc Anderson - Bowra Station, Queensland, Australia Fernand Deroussen - Kinleith, Waikato, New Zealand

One of Australia’s commonest ducks, Grey Teal is a plainly-plumaged species, often difficult to distinguish from the closely-related Chestnut Teal. It is a gregarious species, with counts of up to 350 birds reported. Grey Teal are common and widespread within Brisbane, although their distribution is usually limited to large stretches of water. This being said, they can wander widely and may occur almost anywhere as a straggler.

An abundant species across much of Australia, the Grey Teal is common across riparian and aquatic habitats throughout Brisbane. Very difficult to distinguish at times from the near-identical Chestnut Teal (Joseph et al. 2009), this species is best identified by being slightly paler overall, with a lighter coloured neck and face; these features are not always definitive (Marchant & Higgins 1990; Menkhorst et al. 2017). Care should be taken when reporting either of these two species, and it must be noted that they are not always identifiable to species level; hybrids between this species and other ducks are rare, but not unheard of, can further complicate matters (Guay et al. 2015; McCarthy 2006).

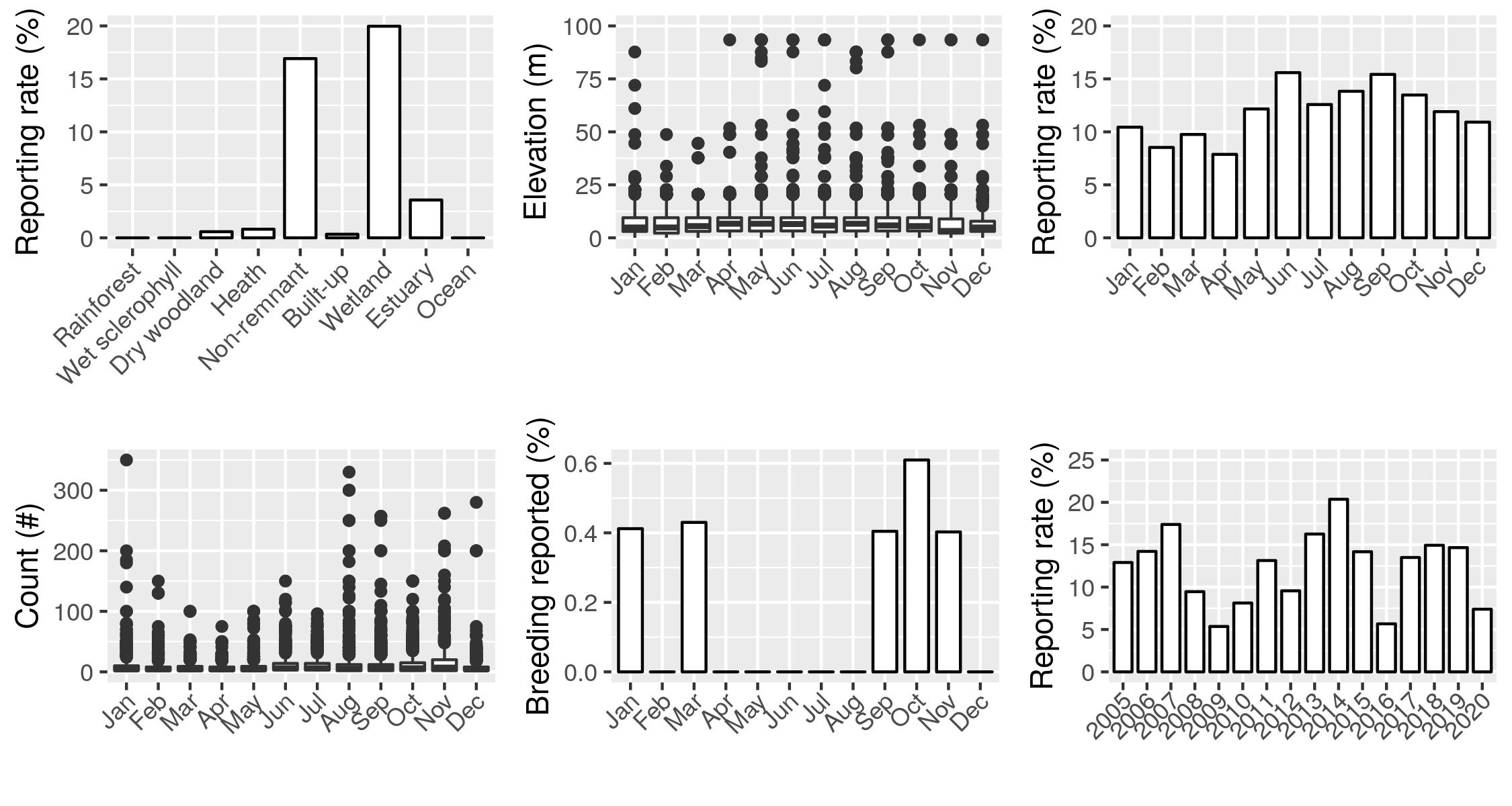

Grey Teal is a gregarious species, with counts of up to 350 birds having been reported (Attewell 2018). The species is widely distributed across the lowlands of Brisbane up to about 150m, and counts of over 200 birds have been reported from 4 locations: Kedron Brook Wetlands, Dowse Lagoon, GJ Fuller Oval Lagoons and Swan Lake at the Port of Brisbane. Birds breed in Brisbane, and breeding has been reported from 6 locations across the region, with most records being of recently fledged young. Teal are present in Brisbane all year-round, although there is a marked increase in reporting rate over the cooler months from May-September, indicating that this species may be a partial winter immigrant.

Although this species appears somewhat dependent on wetland habitats, which are threatened by modification and destruction, birds appear to be quite well-adapted to artificial environments and well-suited to suburban living. As a result, this species’ status within Brisbane appears stable at this time. Nonetheless, care is needed to maintain high quality wetlands, natural or artificial, that are suitable for waterfowl. Of particular importance are the sites this species is most common at, for example Kedron Brook Wetlands, Dowse Lagoon and Prior’s Pocket.

Distribution and Habitat

Grey Teal are found all across Brisbane wherever there is water, especially along the Brisbane River and the coastal wetlands of Moreton Bay from Tinchi Tamba in the north to Mookin-Bah in the south. They appear to be more or less absent from the well-forested north west of the region, and are probably best described as uncommon on Moreton Island (Vernon & Martin 1975), although very few data exist for this region of our city. Grey Teal are more or less a lowland species within Brisbane, occurring at a mean elevation of under 20m; the highest records come from the Lake Manchester region, with birds being reported up to 175m in altitude. Their altitudinal distribution is presumably driven by the availability of suitable waterways and wetlands, which are more or less absent in the elevated parts of the city.

Birds have been reported from a wide variety of habitats, but are by far the most common in non-remnant and wetland environments, where the reporting rate is approximately 20%. Their geographic distribution across Brisbane is presumably mostly driven by the availability of such habitats. The distribution of Grey Teal within the city shows no clear seasonal variation, with approximately the same areas occupied throughout the year, despite birds being significantly more regularly reported over winter.

Furthermore, this species is known to be highly nomadic (Roshier et al. 2008, 2006; Mills 1976), with birds wandering widely in search of water during times of drought. While Brisbane’s climate and landscape is vastly different to that found across inland Australia, where this species is widely found, it is likely that Brisbane’s population has some connection to the inland birds, and as a result Brisbane’s birds may move inland during boom periods of widespread rain and flood. On a more local level, it is likely that birds wander widely across the city in search of optimal habitat, although more fine-scale monitoring is needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Seasonality and Breeding

Grey Teal are quite a seasonally-variable species within Brisbane, being much more common over the cooler months of the year. The reporting rate between May and September is over 15%, while across the rest of the year it is somewhat lower; during January and February birds are only reported on 7.5% of checklists. This indicates that a large proportion of Brisbane’s population are migratory, presumably moving outside the Brisbane region in spring and returning in autumn to spend winter near the coast. It is not currently known, however, where the birds go, and how regular this movement is. Given that the breeding season for this species is generally over spring and summer, this indicates that many birds move inland to breed, with only a handful of breeders remaining to breed in Brisbane. Much more work is needed to determine the specific nature of this pattern.

As noted above, Grey Teal are highly nomadic birds, and their distribution typically follows that of recent rainfall. Brisbane’s birds have been found to disappear with the advent of rainfall further inland (Woodall 1985), and birds have been known to move several hundred kilometres in a matter of days following heavy rain (Marchant & Higgins 1990). As a consequence of this, the overall distribution and abundance of Grey Teal in Brisbane is likely highly variable, and seasonal patterns of abundance (i.e. birds being on average more regular during winter) are likely a result of long-term climactic trends affecting the movements of this species across the whole of Australia. Clearly, much more work is needed in this area!

There are fewer than 10 confirmed reports of Grey Teal breeding in Brisbane, a low result for such a widely-distributed and common bird. As noted above, this is likely a result of birds typically moving elsewhere to breed, with only a handful of birds remaining in the region over the breeding season, and fewer still choosing to breed here. Breeding has been reported from six locations, widely distributed across the region from Prior’s Pocket in the south west to Kedron Brook Wetlands in the north east. It would be good to collect more breeding information about this species within Brisbane, and conduct some specific surveys for this species over spring and summer to determine how many birds do breed, and if prevailing climactic conditions inland affect these numbers.

Trends

As would be expected for such a strongly-nomadic and likely migratory bird, the annual reporting rate for Grey Teal in Brisbane has been highly variable over the Atlas period, with some years having birds being reported on 20% of checklists and others as low as 5%. Of note were the years 2009 and 2016, where birds were reported on just 5% of checklists in each year. 2016 was characterised by well-above-average rainfall across the majority of inland Australia and drier-than-usual conditions in south east Queensland, suggesting that Brisbane’s birds may have moved inland for much of the year to capitalise on favourable conditions (Meteorology 2017). 2009, on the other hand, was a more varied year, with south east Queensland receiving slightly below average levels of rainfall, most of inland Australia record significantly below average levels but the Gulf of Carpentaria receiving very large quantities of rain, as much as 200% of the annual average (Meteorology 2010). It is therefore possible that Brisbane’s birds moved north during the wet season to make the most of conditions there.

Such nomadic movements are well-known in the literature, as discussed above, and Brisbane’s birds have been found to move outside the region during periods of heavy inland rain (Woodall 1985), suggesting that great variation in annual abundance is not unusual. It would, however, be good to quantitatively assess the nature of such movements, and to determine where Brisbane’s birds go when they move outside the region. Nomadic birds may be understudied compared to species which are regular migrators or resident (Yarwood et al. 2019), and it is likely Grey Teal, given their significant levels of nomadism, are affected by this phenomenon; the true extent and nature of their dispersal from Brisbane to broader Australia is almost certainly very poorly understood.

Grey Teal are not of any significant conservation concern in the sense that Brisbane’s population is rather peripheral to the main distribution of the species in Australia, and the overall population appears to be fairly stable over time. However, anthropogenic climate change is likely to significantly impact this species’ survival, both in Brisbane and across Australia. As the climate warms and dries, birds will likely be restricted more and more to localised sources of permanent water, rather than being able to survive in a boom-or-bust manner on temporary waterholes across inland Australia. As such, the distribution and abundance of this species, both within Brisbane and more broadly across Australia, should be monitored closely for any signs of population declines.

Information Gaps

- Confirm whether Brisbane’s birds move inland during favourable conditions

- Determine the extent of any regular migratory behaviour in this species

- Determine the key motivators behind this species’ movements throughout the country and within Brisbane

- Determine whether Brisbane’s birds move around locally, and what factors affect their local distribution

- Collect more breeding information for this species within Brisbane

- Understand what proportion of birds move inland or elsewhere to breed and what proportion remain in Brisbane

Key Conservation Needs

- Monitor the species’ population across Australia for any declines

- Protect this species’ habitat at key sites within Brisbane

Contributors to Species Account

Louis Backstrom

References

Joseph L, Adcock GJ, Linde C, Omland KE, Heinsohn R, Terry Chesser R & Roshier D (2009) A tangled tale of two teal: population history of the grey Anas gracilis and chestnut teal A. castanea of Australia. Journal of Avian Biology, 40, 430–439.

Marchant S & Higgins PJ (1990) Handbook of Australian, New Zealand & Antarctic birds. Oxford University Press.

Menkhorst P, Rogers DI & Clarke R (2017) The Australian Bird Guide. CSIRO Publishing.

Guay P-J, Monie L, Robinson RW & Van Dongen WF (2015) What the direction of matings can tell us of hybridisation mechanisms in ducks. Emu, 115, 277–280.

McCarthy EM (2006) Handbook of avian hybrids of the world. Oxford University Press.

Attewell C (2018) eBird Checklist: http://ebird.org/view/checklist/S41796025.

Vernon D & Martin J (1975) Birds of moreton island and adjacent waters. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, 17, 329–33.

Roshier D, Asmus M & Klaassen M (2008) What drives long-distance movements in the nomadic Grey Teal Anas gracilis in Australia? Ibis, 150, 474–484.

Roshier D, Klomp N & Asmus M (2006) Movements of a nomadic waterfowl, Grey Teal Anas gracilis, across inland Australia–results from satellite telemetry spanning fifteen months. Ardea, 94, 461–475.

Mills JA (1976) Status, mortality, and movements of grey teal (Anas gibberifrons) in New Zealand. New Zealand journal of zoology, 3, 261–267.

Woodall PF (1985) Waterbird populations in the Brisbane region, 1972-83, and correlates with rainfall and water heights. Wildlife Research, 12, 495–506.

Meteorology B of (2017) Annual climate statement 2016.

Meteorology B of (2010) Annual Climate Summary 2009. Australian Government.

Yarwood MR, Weston MA & Symonds MR (2019) Biological determinants of research effort on Australian birds: a comparative analysis. Emu-Austral Ornithology, 119, 38–44.