Spiny-cheeked Honeyeater Acanthagenys rufogularis

Category A; Vagrant.

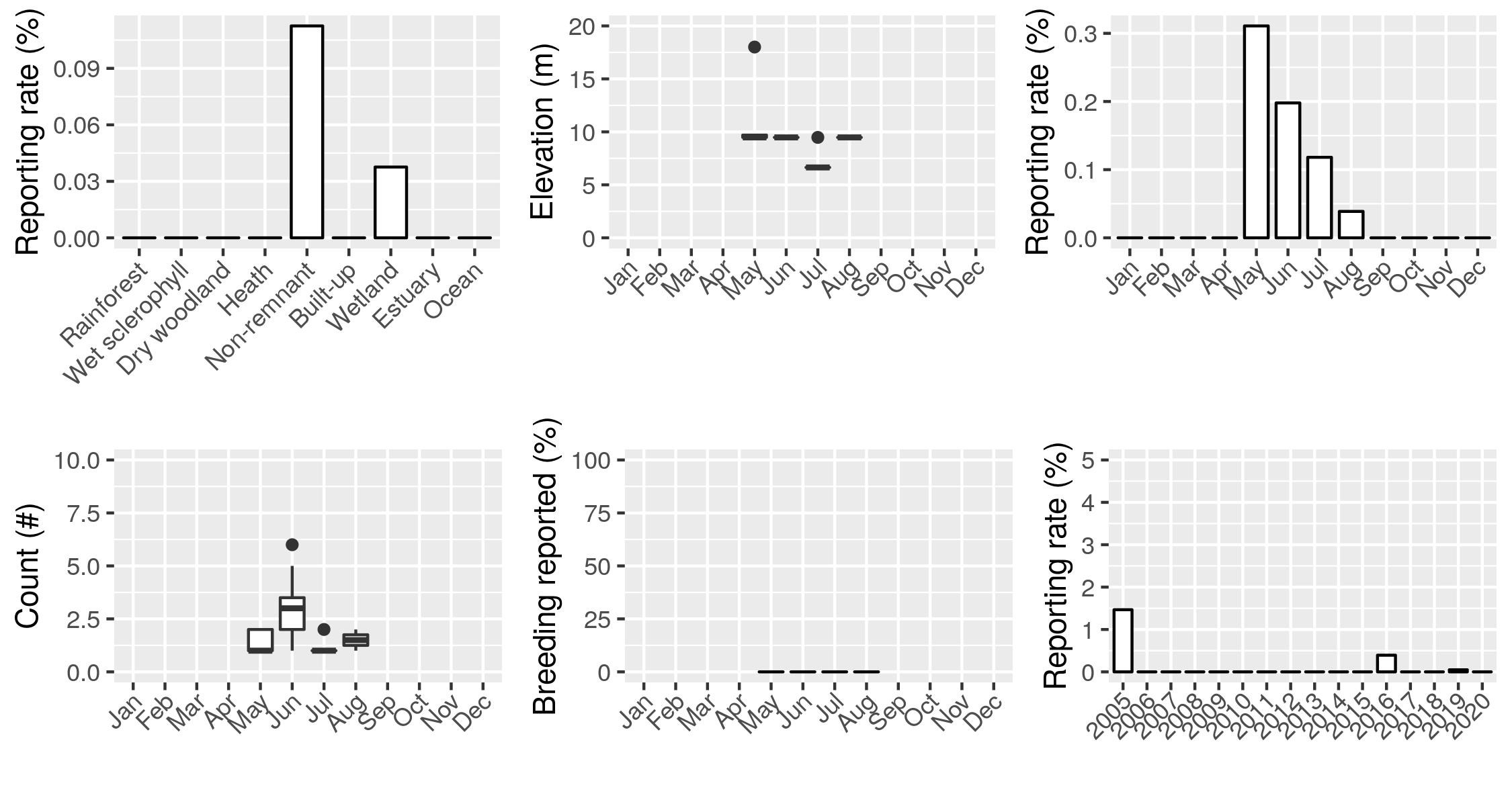

Rare vagrant to the Brisbane region, with only a handful of records, all in winter months indicating seasonal movements. Common throughout the interior of Australia but rarely makes it to the coast.

| Threat status | Brisbane status |

|---|---|

| IUCN Least Concern | eBird records 43 |

| National Not listed | Atlas squares 4 |

| Queensland Not listed | Reporting rate 0% |

Greg McLachlan - Bowra Station, Queensland, Australia

The Spiny-cheeked Honeyeater is a large, distinctive species of honeyeater similar (and closely related) to wattlebirds, with a distinctive tawny breast and throat (Menkhorst et al. 2017). It is gregarious in its normal range, although the majority of records in Brisbane have been on single birds or occasionally pairs. Further birds may turn up anywhere across Brisbane, although there appears to be a preference for open woodland and dry forest, habitat similar to that found in their normal breeding range (Higgins et al. 2001).

A gregarious and conspicuous honeyeater of inland Australia, Spiny-Cheeked Honeyeaters are but a rare vagrant within Brisbane’s environs. In their normal range, they favour open habitats (Higgins et al. 2001) including woodland and grassy savanna, a preference somewhat reflected in their occurrences so far in Brisbane. Birds are nomadic across much of its distribution (Higgins et al. 2001), particularly in the north of Australia, although the provenance of all Brisbane birds is unknown. The species is readily identified by its size (large compared to most honeyeaters), distinctive call and plumage pattern.

Given their nomadic and irruptive nature, it is a little surprising that they have not yet turned up in the west of the city in areas such as Lake Manchester and Anstead, although due to the higher activity by birders at Oxley Creek Common and Tinchi Tamba (where the most records have come from), it is perhaps simply a matter of time and favourable conditions. To date, this species is an exclusive winter vagrant to Brisbane, with the earliest record in mid-May (Hewson & Wilesmith 2016) and the last in mid-August (Possingham 2016). Given that the interior is drier in the winter months and food is scarcer due to decreased flowering, this is likely the driving force behind this species nomadic movements to the coast.

Distribution and Habitat

Spiny-cheeked Honeyeaters are found commonly across much of inland Australia, except in the north beyond about Townsville (~19 degrees south) and in the deserts. They can be found anywhere there is suitable habitat, with no clear elevational preference aside from the intrinsic differences in habitat associated with such variance. A nomadic and gregarious species, they can turn up anywhere at any time with the arrival of budding flowers, and such flowering events are likely to have driven their previous occurrences in Brisbane. They may be more common in the west of Brisbane than current data would indicate, and with increased observer activity in regions such as Anstead, Moggill and Lake Manchester, it seems likely that the odd bird will turn up in dry winters.

Seasonality and Breeding

As mentioned above, Spiny-cheeked Honeyeaters are exclusively winter vagrants to Brisbane, likely due to climactic variations in the interior where they are resident. Not much is known about the specifics of their movements, nor where the birds that have occurred in Brisbane came from. Notably, the majority of records in Brisbane are from 2016, with a prior influx in 2005 indicating that the birds are only rare vagrants to the region. More work needs to be done on detecting any occurrences and identifying the conditions that cause them to turn up.

Trends

As the species is a rare vagrant, no clear trends in the reporting have been identified other than those outline above in the Seasonality section.

Information Gaps

- Find more birds and document them fully with detailed notes

- More audio and photo records, as these are currently lacking from the Brisbane dataset

- Understand where Brisbane birds come from and what drives their movements

Key Conservation Needs

- Protect remnant bushland habitat that favours the birds

- Ensure that there are enough flowering trees to provide adequate food.

Contributors to Species Account

- Louis Backstrom

References

Menkhorst P, Rogers DI & Clarke R (2017) The Australian Bird Guide. CSIRO Publishing.

Higgins PJ, Peter JM & Steele WK (2001) Handbook of Australian, New Zealand & Antarctic birds. Oxford University Press.

Hewson A & Wilesmith W (2016) eBird Checklist: http://ebird.org/view/checklist/S29667767.

Possingham H (2016) eBird Checklist: http://ebird.org/view/checklist/S31038450.