Spangled Drongo Dicrurus bracteatus

Category A; Common widespread partial winter migrant.

Widespread and common breeding resident and partial migrant in varied habitats. More records in autumn in winter and some evidence of altitudinal variance over the year. Not of conservation concern and population appears stable.

| Threat status | Brisbane status |

|---|---|

| IUCN Least Concern | eBird records 15,094 |

| National Not threatened; Marine; Not migratory | Atlas squares 301 |

| Queensland Not listed | Reporting rate 21% |

The Spangled Drongo is a distinctive glossy-black species of Drongo with all-black plumage and a conspicuous forked fish-tail. It is quite a gregarious species, being often reported in counts of 5-10, though large flocks over a dozen are rare. Drongos are common across all of Brisbane in nearly every habitat, including non-remnant suburban parks and gardens.

A noisy, conspicuous species of varied habitats across coastal north east Australia and Indonesia, Spangled Drongos are abundant across much of Brisbane and have been reported from every corner of the LGA. They are seemingly well-adapted to life in suburban Brisbane, where they are common across the city’s parks and gardens provided there is a degree of tree cover available for them.

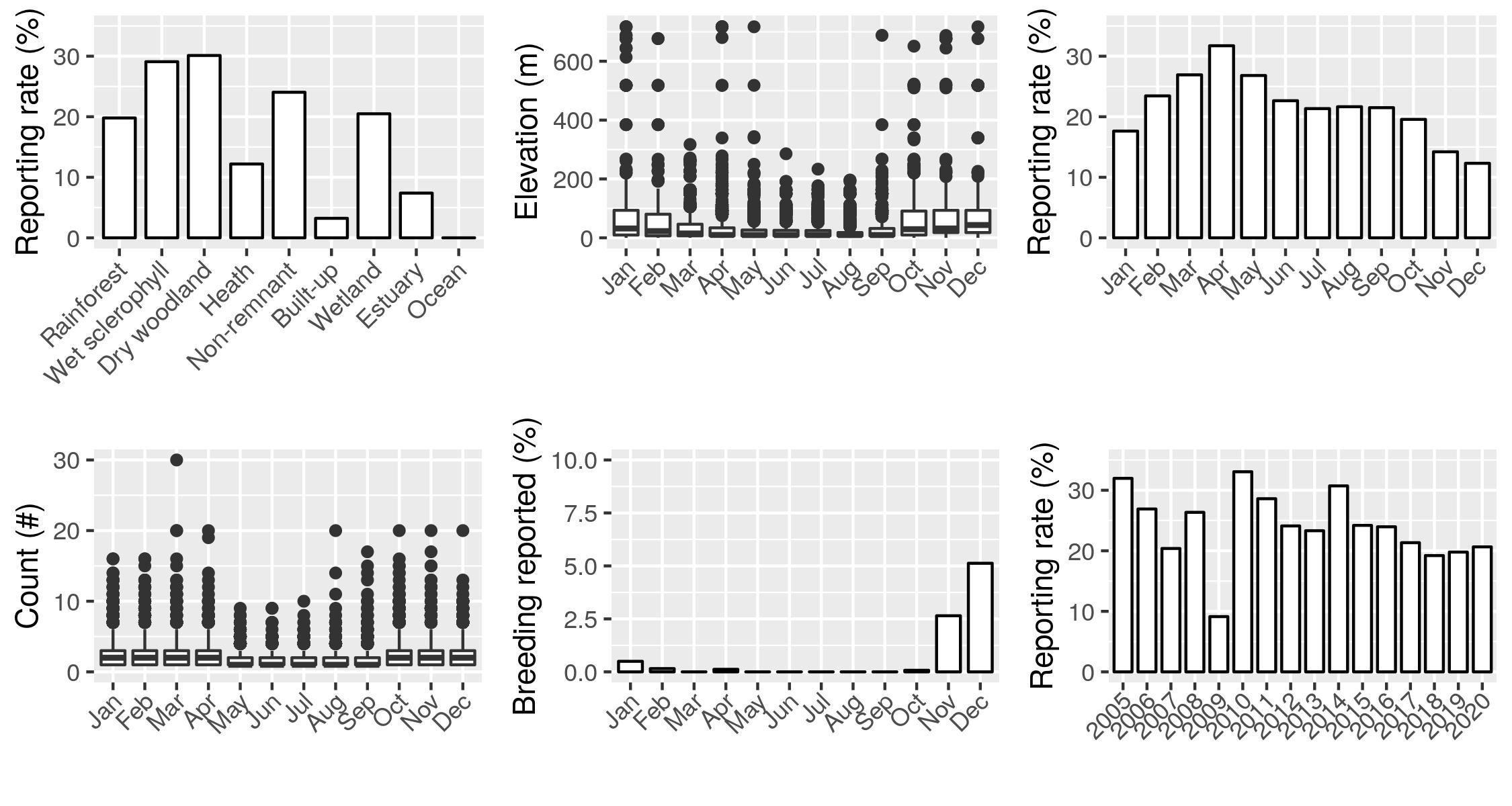

While Drongos are frequently found in pairs or small groups rather than alone, they are not typically found in large flocks, with counts of over 15 being quite rare. The highest count in Brisbane is of 30 birds at Minnippi Parklands on 18 March 2012 (Miller 2012). Counts of 20 birds have been recorded from 4 further locations - Sandy Camp Rd Wetlands, Anstead Bushland Reserve, Gold Creek Reservoir and Hawkesbury Rd Nature Reserve. Spangled Drongos are present in Brisbane throughout the entire year, but there is a clear peak in reporting rate over autumn-winter, with birds approximately twice as abundant as they are in late spring-early summer.

While Spangled Drongos appear to be well-adapted to built-up areas across suburban Brisbane and wider Australia, they are nonetheless better suited to remnant habitats and are somewhat at risk (although not to the same extent as many of our other native species) of further loss of prime habitat. While the expansion of Brisbane’s urban footprint seems likely given our rapidly increasing population, protection of wild areas and planting of native trees and plants in gardens will make a significant difference to the long-term outlook of this species and many others.

Distribution and Habitat

Spangled Drongos are found all across Brisbane, from the high altitude forests of the Camel’s Head to the lowland scrub of Moreton Island and all habitats in between. They are spread relatively evenly across elevational gradients in Brisbane, having occurred from sea level to above 600m with an average altitude of approximately 30m. There is some seasonal variation visible in the elevation of records, with the warmer months typically being higher in elevation (all records over 300m are from September-May); records in November-January have an average elevation of ~50m, while records in May-August have an average elevation of below 10m.

Drongos have been reported from nearly habitat in Brisbane, with the exception of Ocean. They are significantly more common in rainforest, woodland, non-remnant and wetland environs, with heath, built-up and estuarine habitats having reporting rates of below 10%. They are most common in wet sclerophyll, where they are reported on just over 30% of checklists. Their distribution in Brisbane is presumably mainly driven by the availability of adequate food sources - insects and nectar predominately - with a secondary requirement for suitable nesting trees over the breeding season.

There is no clear geographical variation in the distribution of Spangled Drongos across the seasons, although given the moderate elevational trend it is likely there is some movement, probably from the western hills into the eastern lowlands and back again, but more data is needed to determine this. Interestingly, perhaps the only visible trend between seasons for this species distribution is an increase in records in the southside of the river in autumn and winter, but once again this is not overly visible or statistically significant with the current available data.

This species is quite well-surveyed across the LGA, although there are two clear gaps in the distribution data - the north west forests including the Camel’s Head, and the majority of Moreton Island. These two regions are poorly surveyed in the Atlas as a whole and would benefit from intense survey effort to discover the birdlife that inhabits them.

Seasonality and Breeding

There are 13 reports of Spangled Drongo breeding activity from Brisbane, all in the months between November and February. Breeding has been reported from 9 locations, with only Anstead Bushland Reserv and JC Slaughter Falls having more than one breeding report. It would therefore be beneficial to collect more breeding data for this species. Nests with young are known from December-January, suggesting an early summer breeding period, which is in line with the season as reported in the literature (Higgins et al. 2006). Interestingly, the breeding season coincides with the lowest reporting rate for the species, indicating that birds are either much less conspicuous during nesting and breeding (possible, but unlikely to be to such a degree), or birds move out of the region / into less visited parts of the region to breed (quite likely).

Furthermore, this species is known to be partly migratory in the south of its range, with birds moving north over autumn to spend winter in north Queensland and Papua New Guinea, before moving back south again in spring to breed (Higgins et al. 2006). Interestingly, the Brisbane pattern seems to be the opposite of this, with an influx of birds over winter rather than an efflux - this is a clear area where some work needs to be done. Additionally, birds appear to be in larger flocks over the warmer months despite being less frequently reported; this may indicate that birds flock together to breed communally (somewhat supported in the literature) or it may be the result of something else entirely. Clearly, much investigation into the seasonal patterns of Brisbane’s Spangled Drongos is needed.

Trends

The reporting rate of Spangled Drongos in Brisbane has remained quite stable over the past 5 years, although prior to that it was significantly more variable; the reporting rate in 2009 was below 10%. The overall trend appears to be stable, with no clear increase or decrease in the reporting rate, although recent years have not been quite as high as in the past. This species is not of any conservation concern in the sense that it is common across much of Australia and islands to the north, and seems quite well-adapted within Brisbane to suburban life, so is less at risk of habitat destruction and population decline than other species.

Information Gaps

- Work out the reason for seasonal changes in reporting rate, average/high count and elevation

- Collect more breeding data for this species

- Collect location data from within the north west forests, Camel Head and Moreton Island

Key Conservation Needs

- Protect remnant habitat and plant native flowering shrubs and trees to provide a stable food supply for this species

Contributors to Species Account

Louis Backstrom

References

Miller R (2012) eBird Checklist: http://ebird.org/view/checklist/S16677257.

Higgins PJ, Peter JM & Cowling SJ (2006) Handbook of Australian, New Zealand & Antarctic birds. Oxford University Press.